- Home

- Lucie Britsch

Sad Janet

Sad Janet Read online

RIVERHEAD BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright © 2020 by Lucie Britsch

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Riverhead and the R colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Britsch, Lucie, author.

Title: Sad Janet : a novel / Lucie Britsch.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019040326 (print) | LCCN 2019040327 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593086520 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593086544 (ebook)

Subjects: GSAFD: Humorous fiction.

Classification: LCC PR6102.R574 S23 2020 (print) | LCC PR6102.R574 (ebook) | DDC 823/.92—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019040326

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019040327

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

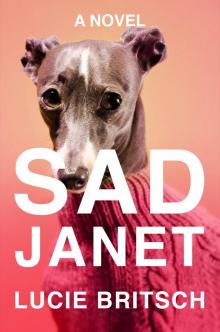

Cover design: Na Kim

Cover image: ULTRA.F / DigitalVision / Getty Images

pid_prh_5.5.0_c0_r0

For the Janets

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Acknowledgments

About the Author

If you just broke up with someone, be sad; if you just ran over somebody drunk driving, feel depressed. You shouldn’t take a pill that makes you feel okay about terrible things.

—John Waters

It’s eight A.M. on Sunday, and I’m taking a dump at work. Or trying to.

Melissa is waiting outside like a dog, or a child, but more like a dog. She’s pretending she needs to go, but she doesn’t. She just wants to know what I’m doing. She’d be in here with me if she could, but there’s barely enough room for one person, never mind two. My knees are almost touching the door. I could whack my head on the sink at any moment. I could do that.

It’s eight A.M. on Sunday, and everyone else in the world is still in bed. In bed is where I left my boyfriend—he’s probably masturbating now—and here I am at work, trying to drop a log. Trying to get a little relief in my otherwise hectic, depression-filled days. I always feel better after. Lighter. Like I’m sending some of the shit that makes me feel this way off to a better place.

But shitting with someone right outside the door is like the opposite of relief.

Leave Janet alone, Melissa, I hear Debs say. Melissa laughs nervously and says she needs to pee, but none of us are buying it.

In this moment, I feel sad for us all. This bathroom is basically a porta-potty stuck on the side of the office. Like they built the shelter and then remembered there would be humans inside it and that sometimes humans need to go.

What are the normal people doing right now? I wonder. How are they starting their days? Getting ready to go to brunch or some other madness. Going to church. Even church might be better than this.

I feel sad for all of us here, having to spend our Sunday listening to me on the toilet.

I wonder if the first person ever to feel sad mistook it for something else. That they needed the bathroom, maybe, or were hungry, or just very tired. We’re all so tired.

Our era will be known as the Greater Depression.

I wonder which came first, happiness or sadness, but I think I know the answer. You assume it was happiness, until something shitty happened and then suddenly, Hi, sadness was there. But I think it started with sadness. That was the first feeling. The first human was like, Wtf is this? Looking at themselves, the world around them—it made no sense, any of it. Sadness was a big gaping hole inside them. But it was also a hole outside them, because human beings hadn’t built anything yet, and they didn’t like all that emptiness or know what to do with it, so they filled it. And only once it was full did they feel happy.

At least for a while.

1

I’m lying in bed watching TV, and some man on some morning show is telling me there are one hundred and eighty-one days till Christmas. I need to be ready, apparently, like there’s a war coming, or a storm. It’s both.

I switch off the man and the TV. I have to get up and get myself to work, and I do both those things and feel like a goddamn hero. My boyfriend does the same, but it’s no big deal to him, which is annoying. He’s annoying.

One hundred and eighty-one days. That’s half a year to worry that I won’t be able to get it up for Santa, or my boyfriend, or myself even. That’s a lot of normal feeling-crappy, with the extra worry that I’ll feel crappy at Christmas, when I’d rather feel something else—not happy, god no, what even is that?, but different. I’ll probably just feel drunk, and then I won’t be able to get it up for anyone, but just let everything happen to me, like most years.

* * *

As soon as I get home from work, I switch on the TV, my only true friend, maybe, since my boyfriend’s not home. I think he said he was doing something, but he lost me at doing. A woman with giant breasts and giant lips comes on the screen. She’s at some kid’s over-the-top birthday party, and she’s saying that life is about being happy. Why isn’t that child in bed? I’m thinking. My only maternal thoughts come at random times, over random things.

She’s from a sex tape. The woman, not the child. She spent all her sex-tape money on this kid’s birthday party. It’s obscene, the party, but she’s happy. The woman, not the child. The child looks crazy. They all look crazy.

I switch off the large-breasted woman and the TV and try to sleep. A hundred and eighty-one days. I need to be ready.

* * *

The next day at work I’m supposed to be brainstorming ways we can get more money, because we have none, but I’m mostly thinking about sadness. Melissa is thinking the shit out of ways we can make more money, any money, and Debs is regretting mentioning it. All of Melissa’s ideas involve us baking, for some reason, but we’re not listening.

I’m thinking about how the world is awful right now, but I think I always knew it was.

For as long as I can remember feeling things, I’ve felt sadness. Now, for example, I feel sad that we have no mo

ney. Also a little mad that a bunch of idiots seem to have it all. But sad, mostly, because I think that’s just the way things are, and baking cupcakes isn’t going to get us enough money to make our lives mean anything.

But that’s not the sadness I’m preoccupied with. Mine isn’t one I can put my finger on. It’s an all-encompassing feeling, like my lungs are filled with it instead of air. It’s not me, but it surrounds me, so it’s become me by osmosis.

You’d think it would feel better to be at one with the world.

People don’t like this sadness of mine. They’ll do anything to pretend it’s not there, that I’m not there. If I hadn’t chosen to work out here in the woods, at a run-down dog shelter, they would have banished me someplace similar, like an outlet mall.

I’m here, though, just barely. Hi.

There’s no word in the English language that properly describes this feeling I have, the one that makes other people uncomfortable. The one that people want me to fix—with makeup, a clean sweater, or a dress, a nice pretty dress, and some girls’ shoes, not boots, not men’s anyway, as if boots give a crap about gender. As if a man can’t wear a dress now. Or a dog.

The Japanese have a term for it: mono no aware, the sadness of things.

The existentialists made it a whole thing—literally made the emptiness of life into a movement—but you have to embrace the sadness to be in their club. I might consider it, if Sartre hadn’t been such a misogynist.

The French call it malaise, I think, which makes it sound like a condiment.

The cool kids call it melancholia, because of that Lars von Trier movie where Kirsten Dunst sobbed at the moon.

The old people used to say bone sad, but I think that was because they were all malnourished and dying of exciting things like rickets and syphilis.

My mother just calls it moody. Difficult.

But the Japanese get it. They have fourteen words for it that don’t exist in the English language, for this feeling that staying afloat is almost impossible.

I’m fine with all of it, whatever you want to call it.

I’m not a goth, though, so there’s hope.

* * *

People are really into this happiness thing, though. They really want me to be happy, and I’m really not that fussed. I’ve dabbled with happiness, I want to tell them, but it never stuck.

I want to say to Melissa, I would fucking love to be thinking about cupcakes and shit right now, but my brain doesn’t work like yours.

Sometimes I think it’s my fault that I let the sadness in. I used to make these crying tapes of sad songs that I’d listen to at night when I was in my bed and supposed to be sleeping but I wasn’t, I was crying. Crying for all the shitty things I knew were coming. I wasn’t even a teenager yet, but I felt tender and raw and open to all the pain. All those dumb songs about love and heartbreak. I should have been listening to the fucking Muppets.

So maybe I willed it to me, the sadness. And since then I’ve been storing it all up when I should have been throwing it out. Hoarding sadness like I think there’ll be a TV show about it one day and someone is about to come and help me sort my life out.

No one is coming.

Melissa is saying something about a car wash now, and it’s gone too far. Like she thinks I’m ever actually going to take my coat off. That underneath this is a bikini body I’ve been hiding and it’s the answer to all our prayers.

A car drives past, and I catch a second of some boy band I shouldn’t know but I do because you can’t avoid them.

I should be happy, apparently. Not because we’ve just won the war on terrorism, or survived a near-fatal collision with an asteroid, or found the cure for cancer, but because happiness is right there for the taking, if I would only take my butt down to my doctor and then to the pharmacy. Even just a smile might do it.

But I can’t find the words for my hollow feeling. What I need is for someone to see me standing here in my giant coat, holding a bag of dog shit, trying to get on with my day, while Melissa talks at me about bake sales and car washes and moonbeams, and to see that I’m not okay with any of it.

* * *

Antidepressants are good now, they say. Real progress has been made.

Melissa is on Lexapro. Debs is on good old-fashioned Prozac; she prides herself on being one of the originals. Whoever was driving that car playing the boy band was definitely taking something. Everyone is taking something but me.

My best friend, Emma, started taking Zoloft because she got a free hat. She wasn’t a hat person, but she thought she might be if she was happier. She never did, but she did feel better, so much so that she ran away to Ibiza and never came back. I can’t even pronounce Ibiza.

On the plus side, there’s no stigma now that everyone’s medicated. It’s a huge relief for a lot of people, and I’m genuinely happy for them. Yay, drugs! It still doesn’t mean I want to take any pills.

No one wants to take pills, Debs says.

She’s wrong. I’ve known people who want to take all the pills. They think if there’s something wrong and there’s a pill, then why not? They take a dozen different ones. My mother’s one of those people. For her, they’re a godsend. I like to remind her that god has nothing to do with it, unless he’s actually some creepy dude in a lab throwing money around. He might be, for all I know.

Why does he have to be creepy? she says, and I think the only man she’s ever met is my dad, maybe.

My dad’s a plumber, but he’s not super or called Mario, so no one thinks it’s funny. When he’s not plumbing, he’s watching TV and drinking and avoiding my mother like the rest of us.

During the holidays, when other kids got jobs at the mall, I went and learned how to fix a faucet and unblock a toilet. My father thought I was just doing it to avoid the mall, and my mother thought I was doing it to spite her. She wanted a daughter who would stay home and tan with her, not one who preferred to spend the day sticking her arm down a stranger’s toilet. The real reason was that I wanted to see how other people lived. I only saw bathrooms and kitchens, but what more was there? They were the hearts of the home and the people who lived there. I saw a lot of shit that Christmas season.

If my mother had had all these pills when she was younger, she might not have had me and my brother. We were supposed to fill some hole, but we didn’t. And yet she still thinks I should have children. It can’t hurt, she thinks, forgetting how childbirth works.

My mother worked for the local council all her life, doing something that required her to wear an ugly pencil skirt and uglier shoes. I like ugly shoes, but these were too depressing even for a funeral. Then everyone lost their jobs because all the council’s money had been mismanaged and she took some different pills and started teaching Jazzercise. Before that, we hadn’t even really known she had legs. Finally, something we had in common.

Neither of my parents had had great Christmases growing up, so they wanted it to be different for us. Which meant they went all out, and we got a shitload of pressure. They thought it was important. More so than our mental health. And the world seemed to agree.

My mother was overcompensating for something—everything, maybe, like everyone else. That was all the holidays were about, filling the void. As a result, Christmas at our house was brutal. Like someone sitting on your chest and punching you in the face repeatedly, but in an ugly snowflake sweater and to the sounds of Dolly Parton singing “Jingle Bells.”

You know Christmas, right? You’ve seen it? It’s such a huge, grotesque spectacle. When you’re a kid, you don’t know any better. It’s just what you do at the end of every year. But my mother was ruining it. The pressure to perform was unbearable. To be not just a happy family but a happy person in the world, because it was Christmas. But all her pills kept her from seeing how it affected me. They kept her going and she didn’t look back. The world was her enabler. It gave her permis

sion to keep shoving it down my throat. You get on the Christmas train, Janet, or we run you over anyway.

Despite all that, I loved Christmas so damn hard, right up to the moment I didn’t anymore. Still, like with all relationships, I kept letting it screw me because I didn’t know how to tell it I wasn’t really into it anymore.

* * *

Of course, my mother isn’t the only one. Every December the world spends screaming: The more the merrier! The bigger the better! Everyone trying to out-Christmas one another. If you aren’t in a festive onesie, grinning because Christmas, you might as well kill yourself. People go into debt for it. People do kill themselves over it. It’s too sad.

The whole world is too sad, really, but no one wants to admit it because they made it that way.

Which is why I spend the holidays feeling like an embarrassment. I’m letting them down. Moping around in the woods, hoping it will all be over soon.

At least I’m not hanging around malls or parks or wherever happy people go, weeping in my funeral clothes, reminding people that sadness still exists. I’m just living my life. I’m here at the shelter mostly, where my sadness isn’t out of place.

There were other people like me for a while. I think of them as the other Janets. People who couldn’t do it. The sad, the bereaved, the lonely. I used to read articles about them, about how awful it was to not feel how they were supposed to at Christmas. But then those articles vanished. It was as if people just didn’t want to hear it anymore. People only wanted the happy stories. New articles came along, ones about sad people who went and got medicated and now could enjoy Christmas again. All of it paid for by the drug companies, I’m sure. But I like to think the Janets are still out there, somewhere.

I hope some of them just ran away, like me.

Sometimes, when I’m walking the dogs in the woods, I see larpers. Debs calls them the fucking larpers, like it’s their family name. Mr. and Mrs. Fuckinglarper. I can be walking along, minding my own business, and suddenly out of nowhere there’s a boy dressed as a knight. He’ll say something like, Sorry, my lady, then bow and charge off, and I’m left there thinking, Boys are fucking weird, but also it’s the most romance I’ve ever had, maybe. Once, a larper came to the door and asked to use the bathroom, and Debs said, If I let you, I have to let all of you, and I don’t want to look like I condone what you do. I have kids.

Sad Janet

Sad Janet